Methodological Seminar - From hunterature to professionalised Ìjálá music: my field experience with Àlàbí Ògúndépò - Dr Olaolu Adekola

On 20 May, we welcomed Dr Olaolu Emmanuel Adekola, an ethnomusicologist from the University of Ibadan, for a Methodological Seminar on "From hunterature to professionalised Ìjálá music: my field experience with Àlàbí Ògúndépò". Delphine Manetta, IFRA-Nigeria deputy-director, opened the seminar with an introduction of Dr Adekola. A graduate of a Bachelor of Arts from Obafemi Awolowo University, he pursued a Masters of Arts and a Ph.D. in African Musicology at the Institute of African Studies (IAS), University of Ibadan. His topics of research are music education, music migration, agromusicology, and he wrote about Ìjálá and Àgídìgbo music. Today, he is a postgraduate coordinator at the IAS, and also teaches postgraduate students. He is a member of Association of Nigerian Musicologists, Society of Music Educators of Nigeria, and a fellow of Ife Institute of Advanced Studies.

On 20 May, we welcomed Dr Olaolu Emmanuel Adekola, an ethnomusicologist from the University of Ibadan, for a Methodological Seminar on "From hunterature to professionalised Ìjálá music: my field experience with Àlàbí Ògúndépò". Delphine Manetta, IFRA-Nigeria deputy-director, opened the seminar with an introduction of Dr Adekola. A graduate of a Bachelor of Arts from Obafemi Awolowo University, he pursued a Masters of Arts and a Ph.D. in African Musicology at the Institute of African Studies (IAS), University of Ibadan. His topics of research are music education, music migration, agromusicology, and he wrote about Ìjálá and Àgídìgbo music. Today, he is a postgraduate coordinator at the IAS, and also teaches postgraduate students. He is a member of Association of Nigerian Musicologists, Society of Music Educators of Nigeria, and a fellow of Ife Institute of Advanced Studies.

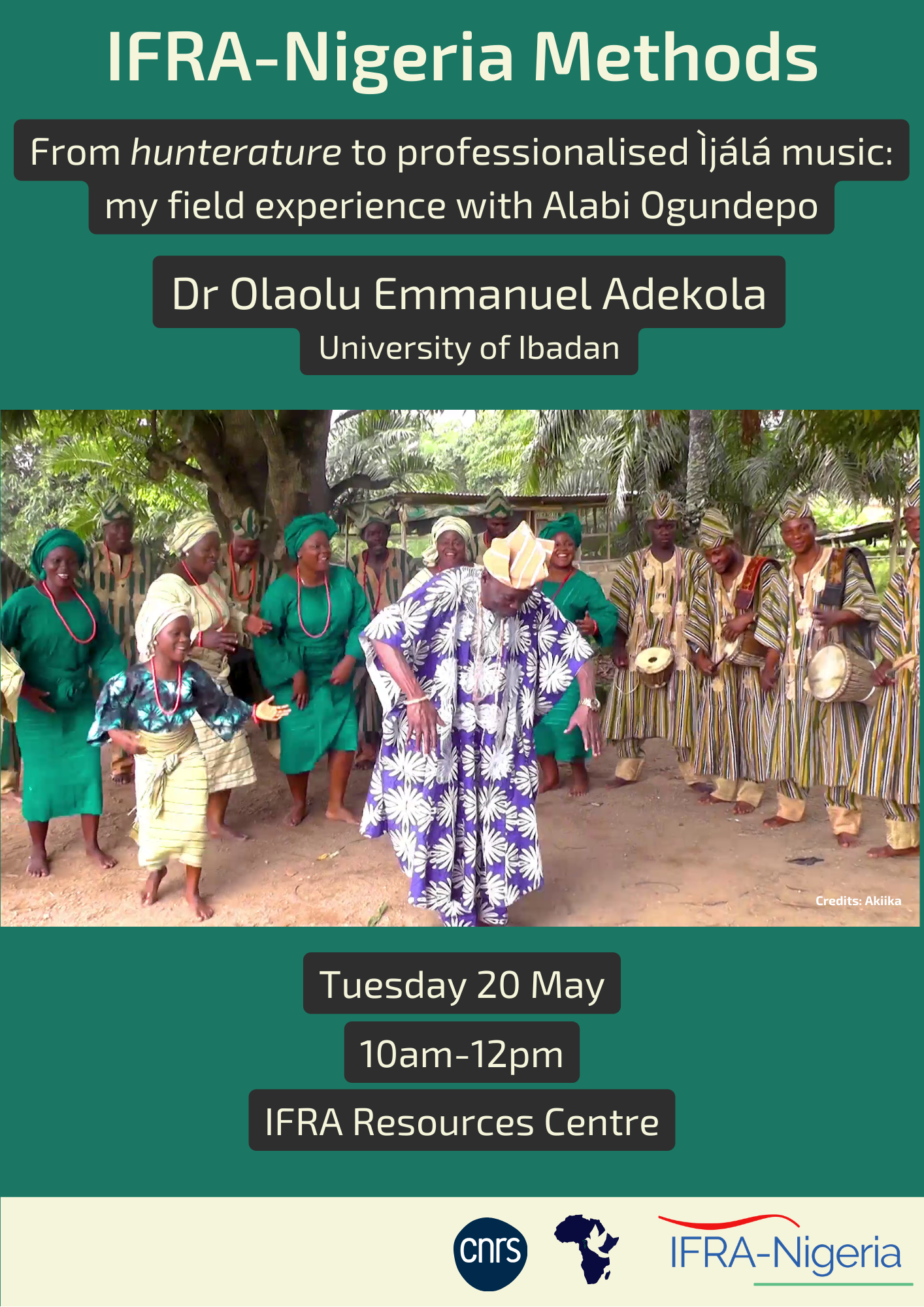

Dr Adekola then screened a video of a performance by Àlàbí Ògúndépò, showcasing his singing and music accompanied by dancers. This introduction, presenting both his topic and medium of his research, was a way to begin identifying significant aspects of the performance. He then explained the terms of the title of his presentation. 'Hunterature' is the practice of hunters to narrate their expedition, including through exaggerated or distorted tells, accompanied by drums. It is also a metaphysical practice, as it arose as a way to gain favour Ogun, the orisha of iron in Yoruba culture, and draws from the belief that hunters have a unique connection to nature. For the purpose of his research, Dr Adekola distinguishes it from what he calls Ìjálá music, its contemporary evolution. The shift from one to the other is inherent to the professionalization of its practitioners, now full-time musicians with a monetary goal, and no longer hunters looking for entertainment alone. Dr Adekola's research focuses on this progressive shift, as well as the impact of the professionalised Ìjálá music on the remaining hunterature performed by hunters. The instruments of the practice also changed: from the traditional Àgẹ̀rẹ̀ drums to the more versatile and broadly-accepted Dùndún drums.

The context of the practice of Ìjálá has also shifted. It was originally a Ìjà ńlá or a 'great contest' between the hunters who would engage in a rhetorical and poetic back-and-forth, showcasing their knowledge of nature, of proverbs and stories, and could be performed after the hunt or at a hunter's funeral. Moving into modernity, Ìjálá is now present in a wide variety of contexts and for different purposes : from warning about road safety on radio, to naming ceremonies and political meetings. It may also be used as a way to decry people's perceived wrongs, women's in particular. While some see this as a breach of tradition, Dr Adekola explains that a researcher's role is to analyse the phenomenon and new ideas, without judgement, in order to understand its dynamics.

Credit: Akiika

He then provided an overview of his process in three moments : pre-field, fieldwork and post-field. Before going on the field, he emphasized the importance of carrying out a very thorough literature review on your subject, and, beyond, starting to conduct your own analysis. Detailing his own experience, he highlighted how collaborating with colleagues was instrumental to make contact with the key informants. Once he completed the background work, he headed to the field with a hired cameraman. There he conducted an interview with Àlàbí Ògúndépò and gathered information through ethnographic observation. He emphasized how important it is for the researcher to interact with humility with his interviewees, and to not take them for granted. One must also be aware of what is polite, the conventions of those you come to study. In his case, in a village, that meant showing what he calls "native intelligence": dressing traditionally, being extremely polite, bringing gifts to the family etc.

His interview style with Àlàbí Ògúndépò was unstructured in order to provide a maximum of flexibility in their interactions. For other researchers using the same method, he noted the paramount importance of already knowing and having deeply studied his topic prior. This allowed him to filter through the massive amount of information, both from observation and interview, but also to conduct the conversation. Indeed, he was able to prompt memories in Ògúndépò because he already knew his songs, but also his sources of inspiration and compositional technique. Thus, patience is key at each stage of the project : while exploring the available documentation, trying to make contact with key informants and in carefully unearthing the data gathered in the field work. As explained by Dr Adekola, the academic shouldn't confuse the mass of information he gathered with data, which are the true building blocks of research.

With the help of a hired cameraman, Dr Adekola also captured his interviews and performances. The recordings played a key role, not only in illustrating his research but also because it allowed him to look back on the nuances of the interactions. The post-field work was therefore spent reviewing the footage and notes, analysing the acquired content and writing his report. In addition, as he was able to capture on film Ògúndépò's singing, the recording is also meant to become an archive of music's history.

To summarize, this new form of Ìjálá allowed the practice to successfully integrate in the modern context, and gain a new form of acceptance and reach to the public. Ògúndépò's artistic innovation contributed to make Ìjálá a philosophical material and an archival document. Concerning his research practices, he reminded us that hard work, the willingness to dig deeper, and proper preparation are the key to a successful field experience. There, your preparation will help filter the relevant information, which can then be transformed in the data and analysis that will make great research. One shouldn't underestimate the social aspect of research, both the collaboration with other researchers, and adapting to your interviewee. Finally, academics must value the contribution of those they interview, without whom research wouldn't be possible, and keep a posture of humility with them.

Janet Ogundairo, IFRA-Nigeria post-doctoral fellow, opened the Q&A session. The lively discussion touched on the possible translation and international broadcasting of Ìjálá; the archiving of the Ìjálá still practiced in villages; how to be accepted in the field, including through gift-giving; the changing place of women in Ìjálá and more.

Social Media

Mailing List